ROBOTS AND HUMANS: LEARNING HOW TO ADAPT NEW TECHNOLOGIES

Author: Esperança Lladó Pascual, Clínica Humana

Introduction

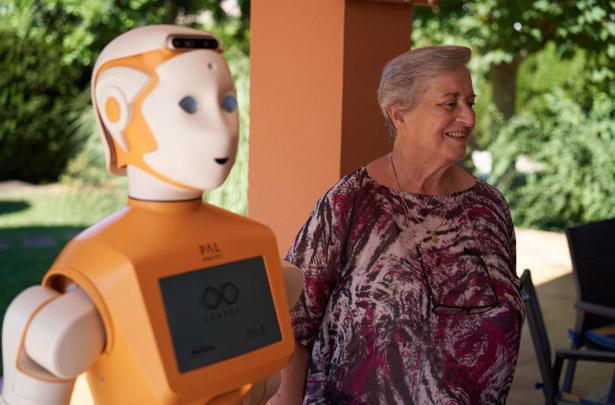

Ca’n Granada is a retirement home in Mallorca, where older adults live in their own apartments, share common areas and have access to services and activities. One of these activities is held every Friday by a psychologist from Clínica Humana who runs cognitive stimulation sessions with the residents. Connecting to the activity, we from Clínica Humana decided to run one of the SHAPES pilot studies called “A robot assistant in cognitive activities for older people” at Ca’n Granada. The hypothesis behind this study is that social robots, in this case the humanoid robot called ARI from PAL Robotics, which is integrated with a set of cognitive activities developed by SciFY, can be an improved channel to provide cognitive training in a more personalised and motivating manner. Therefore, the main goal of this study was to evaluate the user engagement and the user-perceived usefulness of the system.

In July 2021, a mock-up presentation was held at Ca’n Granada, where three older persons assisted. In that session we introduced ARI to participants through a Power Point presentation, showing them pictures and explaining what the robot could do and how it could be a useful tool to assist in cognitive training. The participants seemed pleased with the idea of using ARI but expressed some critical opinions about the physical shape of the robot, such as “ARI is big, and the eye movements are disturbing” and voiced doubts about the use of the robot, such as “I would prefer to do the activities on paper” or “I would like to use it during the cognitive sessions with the psychologist, not on my own”.

“I would like to use it during the cognitive sessions with the psychologist, not on my own.”

Feedback

The feedback we collected during this first session was useful to understand what features needed to be adapted. We passed all the comments to the technical partners and together made the corresponding changes: PAL started to develop a new eye design for ARI, we defined a new game structure based on the participants’ suggestions, including the option to print the game to do it on paper, and we planned with the psychologist how to implement ARI in the regular cognitive sessions.

Few months later, after implementing the feedback collected in the mock-up training, we decided to do the hands-on workshop. At this point, most of the participants in the mock-up presentation were no longer living at Can’n Granada so the hands-on session would be held with other participants. In her next cognitive session, the psychologist informed the new attendees that their next cognitive training session in December would be supported by an assistive robot and, even if they didn’t have any previous knowledge about the robot, they agreed to the idea.

When the day arrived, we entered the room, this time bringing ARI with us to do the practical session. Five participants were already there and after a brief introductory conversation, one of the residents started a discussion about the recent introduction of robots in some areas, saying that he did not like the idea of robots taking over. Two of the other participants in the room joined the conversation while the other two remained silent. The participants started to get a little bit annoyed with the situation and expressed their opinions loudly saying;

“I don’t like talking to robots”, “I want to come to the cognitive sessions, not to do them with a robot”, “Robots don’t have feelings”, “Robots are replacing people’s jobs”, “I don’t like using new technologies”, “I like talking to people not machines”.

We didn’t interrupt them but listened attentively to their feedback and worries and provided space for them to express their opinions. Only later we intervened to clarify that a robot was a tool, just like Power Point was in their current sessions, and that Clínica Humana’s intention was to find out whether, and in what ways, it could be most helpful.

At that point, the psychologist leading the regular cognitive sessions, entered the room, introduced us, and tried to recreate a more relaxed atmosphere. Then, we started distributing the consent forms but soon the previous conversation started again. The psychologist reminded the residents that this was only a demo and that everyone was invited to share their views on what they liked or didn’t like about it. However, the conversation continued to circle around the same points until the residents didn’t seem to be willing to participate in the session anymore. Aware of the situation, we rethought the approach and, highlighting again the voluntary nature of the study, asked the participants directly about their wish to participate in the robot assisted session. Three persons answered that they would prefer to do the usual cognitive session; the other two were asked again directly and nodded, they agreed with their colleagues.

Unfortunately, given the residents’ reactions, we were unable to complete the session. Seeing the experience as an important learning opportunity, we have since attempted to understand the reasons why this hands-on training wasn’t successful. After analysing the situation, we have realised that new technologies need to be adapted to the users of today, responsive to their real needs and social situations, and take into account their fears and concerns. For example, after the attempt, the psychologist told us that just before our arrival some of the residents had expressed their doubts about robots. This was to be expected as they had not participated in the mock-up presentation and therefore lacked proper introduction to the tool and its functions. Also, there was a room change in the last minute, which could have been another unsettling factor. Furthermore, the fact that some of them had already participated in another hands-on training for another SHAPES use case with the robot ARI may have overwhelmed and confused them. The most important reason, however, seems to be a genuine fear of robots replacing the human interaction with the psychologist during the weekly sessions.

Conclusion

Failures are written up in the scientific literature far less frequently than successes, but failure is a great teacher, without which no progress is possible. Working in a real-life situation with the residents at Ca’n Granada, we have learnt some key lessons: to empathise with the intended users, to consider their believes, opinions and concerns, and to think carefully about the way in which new technologies are being introduced. Now, thanks to this enlightening experience, we are confident that we can find the way of fulfilling the user needs and to create a positive and joyful human-robot interaction.

Category

Release Date

April 2022

Useful Links/References

- Dratsiou I, Varella A, Romanopoulou E, Villacañas O, Cooper S, Isaris P, Serras M, Unzueta L, Silva T, Zurkuhlen A, MacLachlan M, Bamidis PD. Assistive Technologies for Supporting the Wellbeing of Older Adults. Technologies. 2022; 10():8. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies10010008

- Chen, Y.R.S. The effect of information communication technology interventions on reducing social isolation in the elderly: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, 4596.

- Shishehgar, M.; Kerr, D.; Blake, J. A systematic review of research into how robotic technology can help older people. Smart Health 2018, 7–8, 1–18.

- Cooper, A. Di Fava, C. Vivas, L. Marchionni, F. Ferro. ARI: the Social Assistive Robot and Companion. 29th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), IEEE, 2020

- https://pal-robotics.com/robots/ari/

- https://www.clinicahumana.es/

- https://www.cangranada.com/