“I Wish to Fall in Love Again”: Loss, Passion, and Sexuality in Later Life

Author: Pedro Rocha, UPORTO

Growing up during the political and economic transformations of Twentieth Century Portugal, many older adults vividly recall living through periods of dictatorship, fascism, nationalism, and paternalist government. Likewise, many experienced transitions and adaptations in family structures, marital arrangements, and in the meanings, rituals and behaviours for performing and expressing love relationships.

Leonor, now aged 66, explains that when she was young, she lived in a rural and conservative village in North Portugal. Until 18 years old, she was brought up by her family and community of friends, church, and local habits to believe that marriage with a “good husband” was the only acceptable practice for expressing love relationships. Marriage was a functional system, an economic unity, where each member had a role. Women, as wives, should be mothers and carers, even if they were workers.

An important element of Leonor’s life has been learning that there are many diverse ways, meanings and practices for crafting and maintaining relationships. During an ethnographic interview, she recalls:

“One time, I was in love with a boy from my village. I didn’t like him as I like my husband, but he was a good person, my friend, and a beauty. I almost got married with him, but I found a letter written between him and a person from my village with information about me. Can you imagine? He was asking people from my village how I was as a ‘good woman’!”

At this point, Leonor had moved away to live in a dense urban area and found herself exposed to a different paradigm of love relationships, based on emotional ties and feelings between individuals rather than arrangement, allegiances, function or economics. In this context, she caught her first glimpse of her future husband, Afonso, when she was member of a local political association during the first heady years of democracy. She describes that first encounter, “I felt something, I couldn’t explain. He affected me, as a person, not only physically”. They initially became friends and then started a romantic relationship. Several years later, they got married.

“When I met him, he was enduring a deep depression, and I was his primary caregiver, like a mother, like a domestic. It’s funny and ironic, because I didn’t identify myself with this women’s role. Do you know why I did that? As a depressive person, as a playboy, as a poet, as a painter, as a journalist, as political militant, as a bohemian, as a humanist… he gave me my first idea about who I am as a woman, and what is the meaning of emotion and passion. Indeed, he was already experienced as a member of the new urban class and generation, politically and cultural engaged and emancipated. And, for me, a young girl from a rural and conservative village, it was a new world that was pushing me towards being myself, rationally and emotionally.”

Leonor and Afonso found each other in the midst of a wide range of opportunities for love and for lovers, “especially for him who had several girlfriends” says Leonor, and within a city and a time where certain groups of young adults were deeply engaged with a new political wave and its freedoms. The forty years of dictatorship had recently ended, and democracy was passionately embraced by many, especially welcomed by those rejecting traditional marriage arrangements in favour of freedom, choice and love as the foundation of relationships.

For these reasons, they didn’t get married quickly. First, “we wanted to live together”. It was an exciting time: the new socio-political ‘wave’, building up the new left and urban generation, political parties (parades, debates, political campaigning); social organisations and civil rights movement. A cultural renaissance in music, theatre, exhibitions nestled alongside other exciting revolutions: disco; co-habitation, holidays with friends, and experimentation with new forms of relationships: free love; free sexuality; trans-sexualities. Leonor recalls that in this time, “we lived as two close partners who intensely shared their own lives with each other”.

After being married for many years, Afonso was unfortunately diagnosed with a neurodegenerative disorder. Before Covid-19, Leonor used to visit Afonso in the nursing home every day, remaining there until he had gone to bed. When she talks about him, she says “when I go to visit him in the nursing home, he always greets me just as he always used to do in the past: ‘you are so beautiful, and it’s so good’. However, I realised that he memorised that sentence for me, and I still love him, but it’s not the same. He still is my great partner”.

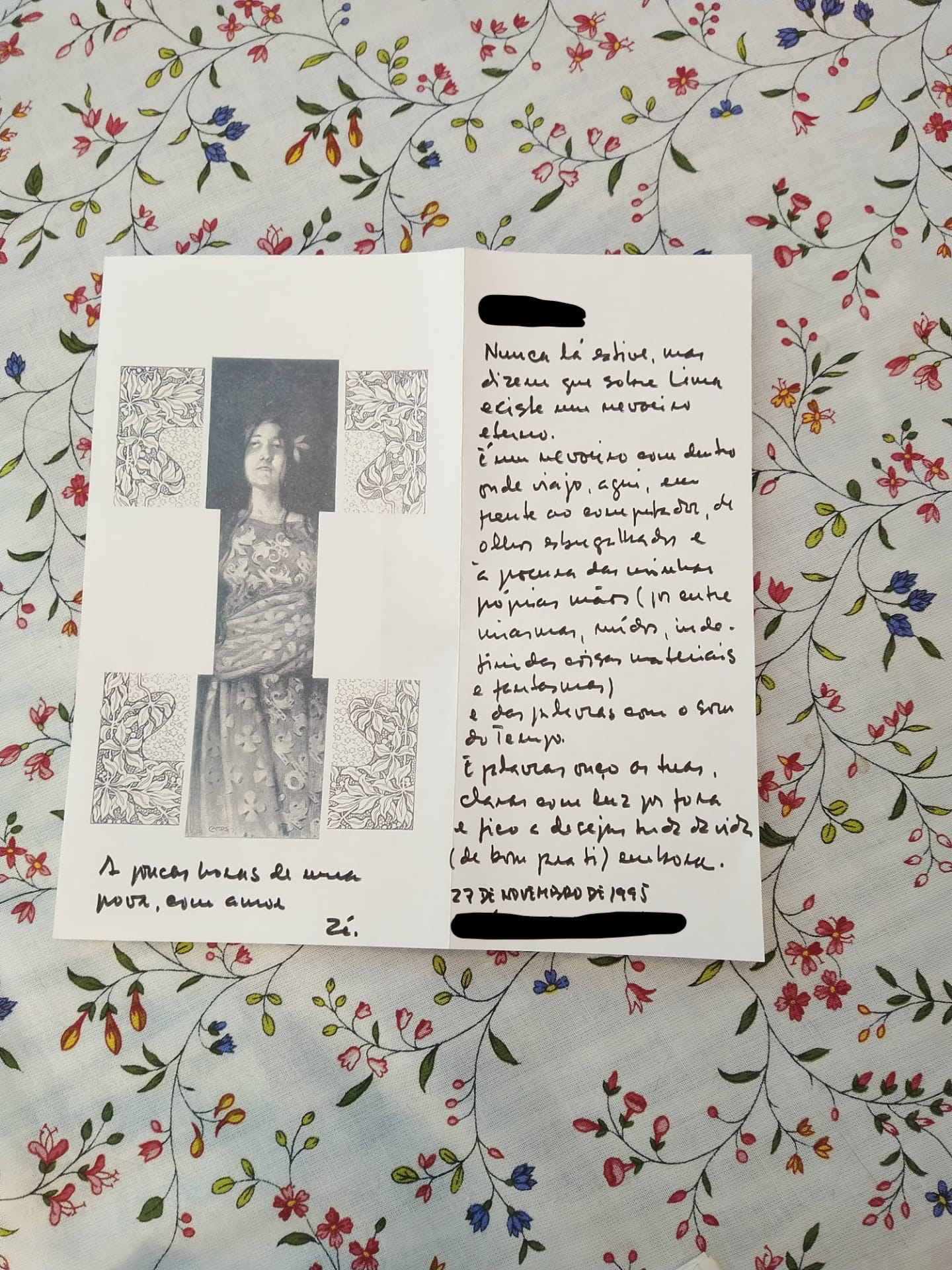

Indeed, their love still exists, but as Leonor reflects, it’s not the same. What and why is it different now? When did things change? “When he was diagnosed with Dementia, I felt bad, but not angry; indeed, we had lived each second of our love, I feel it”. They still love each other. However, things are different. There is love, but she explains that she feels they no longer share emotions, partnership, experiences, and sexuality. This is a great loss and hole in Leonor’s life. She muses, “despite his physical daily absence, my husband still affects me emotionally. I miss the romantic notes left by him during my daily routines: night table, entrance hall, coat pockets, napkins… He misses me, yet.”

Her love for her husband is still meaningful today and whilst she didn’t want a different person(ality) she remarks that “I wish to fall in love again”. Love, passion, feelings and sexuality are not the province only of the young. In fact, one friend of Leonor did try to encourage her to find someone else with whom she could live and enjoy life.

“She convinced me to use a new smartphone App., called Happn, which could help me to meet with someone. ‘It’s funny’ she told me. And, I confess to you, I used it once.”

Asked to elaborate about her experience using a dating App, she became shy but responded: “No, it didn’t work! But let me explain the context. A friend of me and my husband, she worked with him a long time, is got divorced and her last boyfriend left her. She is younger than me and she used that App for meeting a man. Once, we were talking about my husband and me and she said ‘you are alive and you are an attractive woman; for sure, your husband would like you to find a new lover’. Then, she showed me the App and installed it on my smartphone. Indeed, I met an older individual, male, a few years older than me, once. We went to a bakery, but he was so boring and a bad experience. I didn’t like it and I uninstalled the App”.

This is a difficult and emotional time for Leonor, a time of loss, love, memory but also desire and yearning. Perhaps influenced by her past and current expectations, her first experiment with technology mediated matchmaking – or rather the human encounter resulting from it – was not successful, though she doesn’t deny the advantages created by a digital solution for meeting new people. It is easy, fast, simple, informal, (almost) anonymous, and useful for those curious but fearful of risks.

As we consider how digital platforms such as Happn, Tinder and Grindr are being used or will be used by older populations, we should consider how different constructions of love relationships have co-existed together. What are the social and cultural structures, histories and narratives of different and diverse older users? What works and when? And, of course, how do we improve these digital solutions, in order to be useful for older individuals?

Category

Release Date

December 2020

Useful Links

https://senioragecarestlouis.com/love-with-the-right-older-person.html